Switching from brand-name tacrolimus or cyclosporine to a generic version can save transplant patients hundreds of dollars a month. But for many, that savings comes with a hidden risk: unstable drug levels, unexpected rejection episodes, or new side effects that weren’t there before. This isn’t theoretical-it’s happening in real time across hospitals and homes.

Why These Drugs Are Different

Cyclosporine and tacrolimus are both calcineurin inhibitors. They work the same way: blocking T-cells from attacking a transplanted organ. But that’s where the similarities end. Tacrolimus is about 20 to 100 times more potent than cyclosporine. A typical daily dose? Around 5 mg twice a day for tacrolimus. For cyclosporine? 150 mg twice a day. That’s a 30-fold difference in pill size and weight. And because they’re so potent, even tiny changes in how much of the drug gets into your bloodstream can make a big difference. Both drugs have a narrow therapeutic index. That means the gap between a dose that works and a dose that’s toxic is very small. For tacrolimus, the target blood level is usually between 5 and 15 ng/mL. Go below 5, and your body might reject the new kidney or liver. Go above 15, and you risk kidney damage, tremors, seizures, or even diabetes. Cyclosporine levels are higher-100 to 200 ng/mL-but the margin for error is just as tight. And here’s the kicker: both drugs are metabolized by the same liver enzyme, CYP3A4. That means grapefruit juice, antibiotics, antifungals, or even some herbal supplements can throw your levels off. But the biggest wild card? Generic versions.The Generic Switch Problem

In 2023, over 92% of tacrolimus and cyclosporine prescriptions in the U.S. were filled with generics. That’s up from less than 30% a decade ago. Insurance companies and Medicare Part D pushed for the switch to cut costs. Generic tacrolimus now costs $300-$500 a month. Brand-name Prograf? $1,200-$1,500. Same for cyclosporine: generic runs $150-$300; Neoral is $800-$1,000. The FDA says generics are bioequivalent. That means, in healthy volunteers, the amount of drug absorbed into the blood is within 80-125% of the brand. Sounds fine, right? Not for transplant patients. A 2022 survey of 1,247 transplant recipients found that 42.7% noticed changes in side effects after switching to a generic. Nearly 1 in 5 had to adjust their dose because their blood levels dropped or spiked. One patient on Reddit, u/KidneyWarrior, switched from Prograf to a generic tacrolimus and saw his levels crash from 8.5 to 5.2 ng/mL in two weeks. He ended up hospitalized for a mild rejection episode. Why does this happen? Different generic manufacturers use different fillers, binders, and coating materials. For cyclosporine, some generics are oil-based; others are microemulsion. Even small differences in how the drug dissolves in your gut can change absorption. Tacrolimus is even trickier-it’s poorly soluble and sensitive to stomach pH, food, and even the time of day you take it.Real Stories, Real Consequences

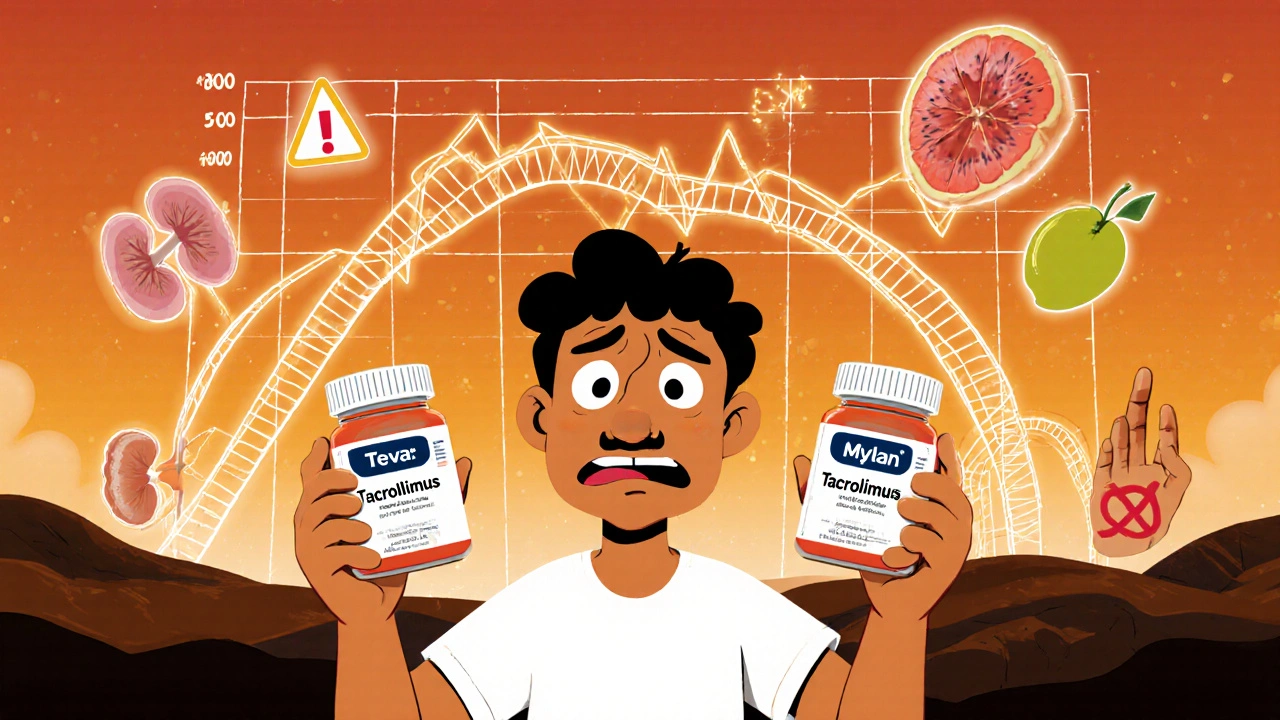

Transplant Living forums have over 300 posts from people who switched generics and saw trouble. Sixty-eight percent reported concerns about effectiveness. One user wrote: “My nephrologist won’t let me switch back to brand because he says I’m lucky to be alive.” Another shared: “I was stable on brand Prograf for five years. Insurance forced me to generic. Within a month, I started having tremors and couldn’t hold a coffee cup. My levels were sky-high. I had to go off work for six weeks.” But it’s not all bad. Some people report no issues. u/TransplantSurvivor on HealthUnlocked said: “I’ve been on generic tacrolimus for 18 months. Levels are perfect. Saved $900 a month.” The difference? Consistency. If you switch from brand to one generic-and stay on that same generic-you’re far less likely to have problems. The real danger is switching between different generic brands. One month it’s Teva. Next month it’s Mylan. Then Apotex. Each has a slightly different formula. Your body doesn’t adapt quickly. And your doctor might not know you were switched unless you tell them.

What Doctors and Pharmacies Are Doing

Most transplant centers now have strict protocols. If you switch to a generic, you get your blood drawn weekly for the first month. Then every two weeks for the next month. Some require a full 6-week monitoring window. Pharmacists are trained to flag any change in manufacturer. But not all pharmacies track that. A patient might get a generic from Walmart one month, then CVS the next-same label, different maker. A 2023 study found that only 41.7% of generic manufacturers provide detailed bioequivalence data to clinics. So doctors often don’t know which version they’re prescribing. The smartest transplant programs now use “single generic source” contracts. They pick one generic manufacturer and stick with it for all patients. That way, if someone has a problem, they know exactly which formula caused it.What You Can Do

If you’re on cyclosporine or tacrolimus, here’s what you need to know:- Know your generic brand. Check the pill imprint or ask your pharmacist. Write it down. Don’t let it change without you knowing.

- Never switch between generics without telling your doctor. Even if it’s labeled the same, different companies make different pills.

- Take your drug at the same time every day, with the same food. Tacrolimus absorbs better on an empty stomach. Cyclosporine can be taken with food-but be consistent.

- Avoid grapefruit, pomelo, and Seville oranges. They interfere with how your body breaks down both drugs.

- Track your levels. Don’t wait for your doctor to call. If you feel off-tremors, headaches, nausea, unusual fatigue-ask for a blood test.

- Ask for a written prescription. Some insurance plans auto-switch you. Ask your pharmacist to hold the brand if your doctor approves it.

The Future: Better Options

In December 2023, the FDA approved a new extended-release version of tacrolimus called LCP-tacrolimus. It releases the drug slowly, smoothing out peaks and valleys in blood levels. That could mean fewer side effects and less sensitivity to generic switches. The European Medicines Agency now requires bioequivalence studies using actual transplant patients-not just healthy volunteers. That’s a big step forward. And researchers are starting to use genetic testing. About 15% of people have a gene variant (CYP3A5*3) that makes them metabolize tacrolimus faster. These patients need higher doses. If you’re tested before starting, you’re less likely to have levels that swing too high or too low.Bottom Line

Generic cyclosporine and tacrolimus are not the same as brand names-and they’re not all the same as each other. They’re close enough to pass FDA tests. But for someone with a transplanted organ, “close enough” isn’t good enough. The cost savings are real. But so are the risks. The key isn’t avoiding generics. It’s controlling the switch. Stay on one version. Monitor your levels. Speak up if something feels off. Your transplant isn’t just a surgery-it’s a lifelong partnership with your medication. Don’t let a pharmacy change that without you knowing.Can I switch between different generic versions of tacrolimus safely?

No, switching between different generic manufacturers of tacrolimus is not safe without close monitoring. Each generic has slightly different inactive ingredients that affect how the drug is absorbed. Even small changes in blood levels can lead to rejection or toxicity. Transplant centers recommend staying on the same generic brand once you’ve stabilized on it.

Why is tacrolimus more sensitive to generic changes than cyclosporine?

Tacrolimus is more potent and has a narrower therapeutic window-target levels are 5-15 ng/mL, compared to cyclosporine’s 100-200 ng/mL. Because the margin for error is so small, even minor differences in absorption from one generic to another can push levels outside the safe range. Tacrolimus is also less soluble and more affected by food, stomach pH, and formulation differences.

How often should I get my blood levels checked after switching to a generic?

After switching to any new generic version, you should have your blood levels checked weekly for the first month, then every two weeks for the next month. Some centers extend monitoring to 6 weeks. Your doctor may adjust your dose based on these results. Never skip these tests-they’re your best protection against rejection or toxicity.

Can insurance force me to switch to a generic?

Yes, most insurance plans, including Medicare Part D, require generic substitution unless your doctor files a medical exception. If your doctor believes switching could harm you, they can submit paperwork to keep you on the brand name. You should always ask your pharmacist if a switch is planned-and confirm with your transplant team before it happens.

What should I do if I notice new side effects after switching generics?

Contact your transplant team immediately. Symptoms like tremors, headaches, nausea, unusual fatigue, or swelling could signal that your drug levels are too high or too low. Don’t wait for your next appointment. Request a blood level test right away. Bring the pill bottle with you so your doctor can identify the generic manufacturer.

Are there any long-term risks of staying on generic immunosuppressants?

There’s no evidence that staying on a consistent generic version increases long-term risks. The problem isn’t generics themselves-it’s switching between them. If you stay on the same generic brand and your levels are stable, your outcomes are just as good as with the brand name. The key is consistency, not the name on the bottle.

Is there a way to avoid generic switches altogether?

Yes. Ask your doctor to write a medical exception letter to your insurance, explaining that switching could put your transplant at risk. Some patients successfully get approval to stay on brand-name drugs due to narrow therapeutic index concerns. You can also contact patient advocacy groups like the National Transplant Insurance Assistance Fund-they help navigate these appeals.

Written by Connor Back

View all posts by: Connor Back