Chronic Diarrhea Risk Calculator

Assess Your Risk

If you’re dealing with chronic diarrhea, understanding its connection to gastroenteritis can help you take the right steps toward relief.

What is Chronic Diarrhea?

When doctors talk about chronic diarrhea, they refer to loose or watery stools lasting four weeks or more. It affects roughly 5% of adults in the UK and can lead to dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and reduced quality of life. Key attributes include:

- Duration: ≥4 weeks

- Frequency: >3 stools per day, often watery

- Potential complications: weight loss, anemia, skin irritation

Because the condition persists, doctors look for underlying triggers rather than treating it as a simple episode of the flu.

What is Gastroenteritis?

Gastroenteritis is an inflammation of the stomach and intestines, usually caused by infectious agents such as viruses, bacteria, or parasites. It’s often called “stomach flu,” though it isn’t related to influenza. Typical symptoms appear suddenly and last from a few days up to two weeks:

- Abdominal cramps

- Nausea and vomiting

- Watery diarrhea

- Fever (sometimes)

Most healthy adults recover without medical intervention, but the infection candamage the gut lining, setting the stage for longer‑term problems.

How Gastroenteritis Can Lead to Chronic Diarrhea

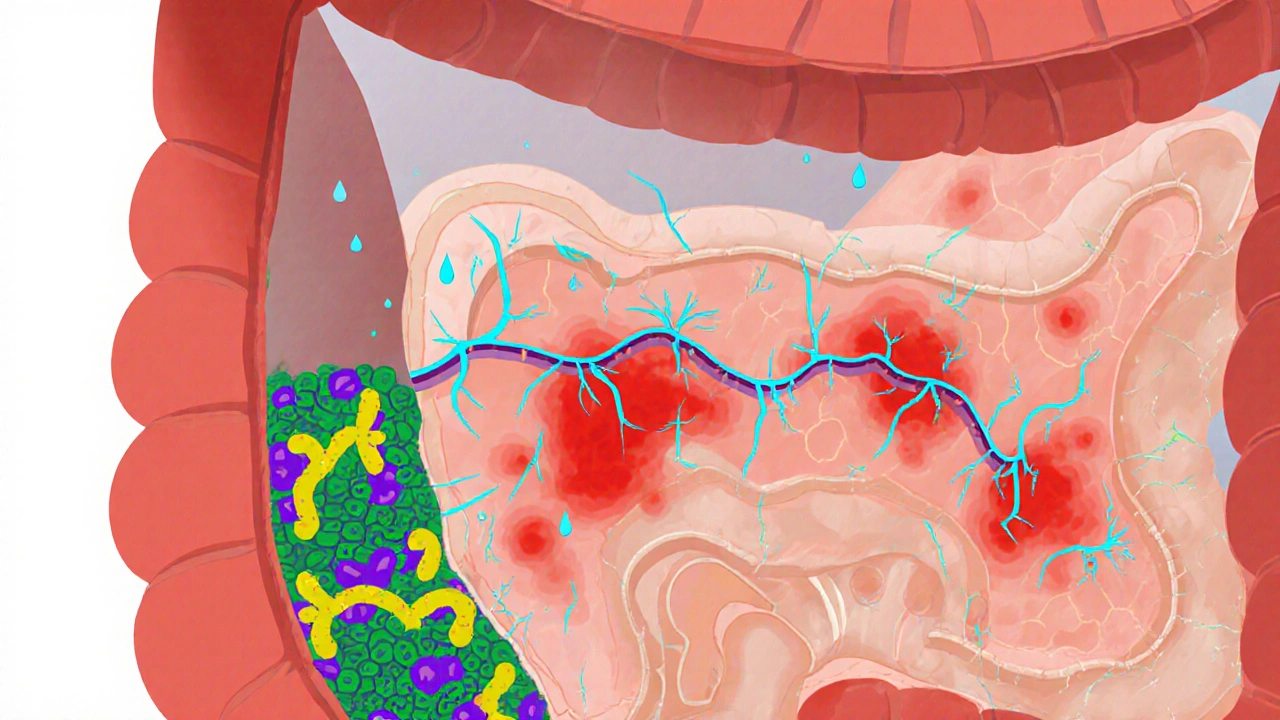

The transition from a short‑lived bout of gastroenteritis to chronic diarrhea involves several mechanisms:

- Post‑infectious inflammation: After the pathogen clears, the gut’s immune system may stay activated, causing ongoing irritation.

- Altered gut microbiome: Infections can wipe out beneficial bacteria, allowing opportunistic microbes to dominate.

- Damage to the intestinal barrier: Tight‑junction proteins can be compromised, leading to increased permeability ("leaky gut").

- Motility changes: The infection may disrupt the nerves that regulate bowel movements, resulting in faster transit.

These changes don’t always reverse on their own, especially if the initial infection was severe or if the person has other risk factors such as antibiotic use.

Common Infectious Triggers

Not all stomach bugs cause long‑term issues, but a few are more notorious:

| Agent | Typical Illness | Likelihood of Chronic Sequelae |

|---|---|---|

| Campylobacter jejuni | Food‑borne bacterial gastroenteritis | High - up to 20% develop post‑infectious IBS |

| Norovirus | d>Viral outbreak in schools, cruise shipsLow - usually resolves fully, but can trigger flare‑ups in sensitive individuals | |

| Giardia lamblia | Parasitic infection from contaminated water | Moderate - chronic foul‑smelling diarrhea common |

| Clostridioides difficile | Antibiotic‑associated colitis | Very high - recurrent diarrhea in 30‑40% of cases |

Understanding the culprit helps clinicians decide whether to target the pathogen directly or focus on restoring gut health.

Overlap with Other Gastrointestinal Conditions

Sometimes chronic diarrhea isn’t purely post‑infectious. It can coexist with or mask other disorders:

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): Post‑infectious IBS is a recognized subtype, especially after bacterial gastroenteritis.

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis may be triggered or unmasked by an infection.

- Antibiotic‑associated diarrhea: Broad‑spectrum antibiotics disturb the gut microbiome, making the gut vulnerable to pathogens like C. difficile.

Distinguishing these entities often requires targeted tests and a careful clinical history.

Diagnosing the Connection

When a patient presents with persistent loose stools, clinicians follow a stepwise approach:

- Medical history: Onset, recent infections, antibiotic courses, travel, dietary changes.

- Stool analysis: Microscopy for parasites, culture for bacteria, PCR for viral genomes.

- Blood work: Complete blood count, electrolytes, C‑reactive protein to assess inflammation.

- Endoscopy (if needed): Visual inspection and biopsies to rule out IBD or microscopic colitis.

- Breath tests: Detect small‑intestinal bacterial overgrowth, which can follow gut injury.

Finding a recent gastroenteritis episode within the past 3‑6 months raises suspicion for a post‑infectious cause.

Managing Chronic Diarrhea After Gastroenteritis

Treatment targets three pillars: rehydration, gut restoration, and symptom control.

- Rehydration: Oral rehydration solutions (ORS) with a 1:1 ratio of sodium to glucose replace lost fluids efficiently. In severe cases, intravenous fluids are required.

- Dietary adjustments: The BRAT diet (bananas, rice, applesauce, toast) can be a short‑term bridge, followed by a low‑FODMAP diet to reduce fermentable substrates that feed harmful bacteria.

- Probiotics: Strains such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Saccharomyces boulardii have clinical evidence for shortening post‑infectious diarrhea and restoring microbiome diversity.

- Medications: Loperamide can control frequency, but should be avoided if infectious pathogen is still present. Rifaximin, a non‑systemic antibiotic, helps in cases of small‑intestinal bacterial overgrowth.

- Address underlying inflammation: In post‑infectious IBS, low‑dose tricyclic antidepressants or gut‑specific serotonergic agents reduce pain and motility spikes.

Regular follow‑up ensures that dehydration or electrolyte disturbances are corrected early.

Prevention Strategies

Stopping the cycle before it starts is possible:

- Hand hygiene: Wash hands with soap for at least 20 seconds after bathroom use and before meals.

- Food safety: Cook poultry and meat to internal temperatures of 75°C, avoid raw milk, and refrigerate leftovers promptly.

- Travel precautions: Use bottled or filtered water, avoid ice in drinks, and carry ORS packets when visiting high‑risk regions.

- Antibiotic stewardship: Only use antibiotics when prescribed for a confirmed bacterial infection; discuss probiotic use with your GP if you need a course.

- Maintain a balanced gut microbiome: Eat a fiber‑rich diet (whole grains, legumes, vegetables) and include fermented foods like yogurt or kefir.

When to Seek Medical Attention

Most episodes resolve, but certain signs warrant prompt evaluation:

- Stools persisting beyond four weeks

- Blood or mucus in the stool

- Severe abdominal pain or cramping

- Signs of dehydration: dizziness, dry mouth, reduced urine output

- Unexplained weight loss of more than 5% of body weight

Early intervention can prevent complications like chronic malabsorption or severe electrolyte imbalance.

Quick Checklist for Managing Post‑Infectious Diarrhea

- Track stool frequency, consistency, and any blood/mucus.

- Stay hydrated with ORS or electrolyte drinks.

- Introduce low‑FODMAP foods after the acute phase.

- Consider a probiotic with proven strains for at least four weeks.

- Schedule a GP visit if symptoms linger past four weeks or worsen.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a single bout of gastroenteritis cause chronic diarrhea?

Yes. In about 10‑15% of people, the infection triggers lasting changes in gut motility or inflammation that keep the stool loose for weeks or months.

What role do probiotics play after a stomach infection?

Clinical trials show that specific strains, especially Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Saccharomyces boulardii, can shorten the duration of post‑infectious diarrhea by 1‑2 days and help restore a healthy microbial balance.

When should I use anti‑diarrheal medication?

If the infection is cleared and you’re dealing only with the symptom of loose stools, loperamide can be used for short‑term control. Avoid it during active infection because slowing gut transit may keep the pathogen longer.

Is dehydration a serious risk with chronic diarrhea?

Absolutely. Ongoing fluid loss can lead to low blood pressure, kidney issues, and electrolyte disturbances such as low potassium, which may cause muscle weakness or cardiac arrhythmias. Replenish with ORS or medical IV fluids if symptoms are severe.

Can diet alone cure post‑infectious diarrhea?

Diet is a cornerstone, but many patients benefit from a combined approach that includes hydration, probiotics, and sometimes medication. A gradual re‑introduction of fiber and low‑FODMAP foods often speeds recovery.

Written by Connor Back

View all posts by: Connor Back