Hyperkalemia Risk Calculator

Assess Your Risk

This tool estimates your hyperkalemia risk based on key factors from the article. It's for educational purposes only - never replace medical advice with this calculator.

Your Risk Assessment

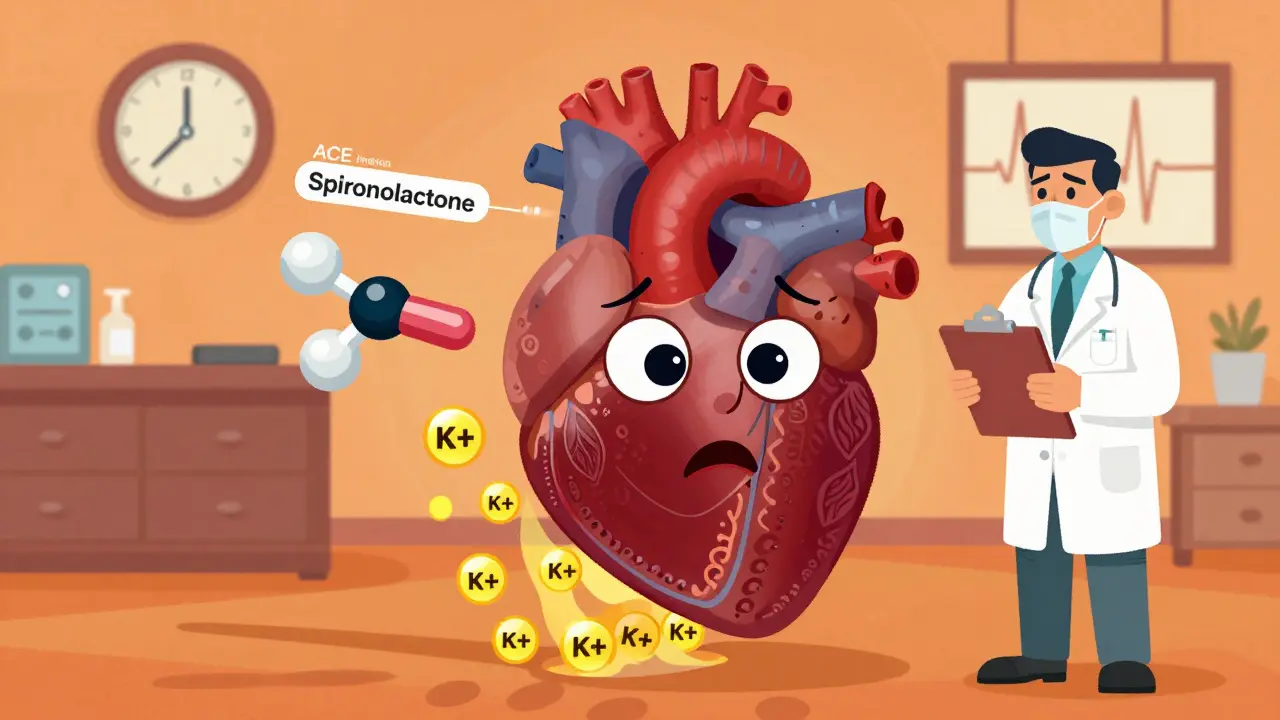

Combining ACE inhibitors with spironolactone can save lives - but it can also put you in the hospital. This isn’t theoretical. It’s happening right now in clinics and homes across the country. Patients with heart failure are being prescribed both drugs because together, they reduce death rates by up to 30%. But for every life saved, another faces a dangerous spike in potassium - a silent, invisible threat called hyperkalemia.

Why This Combo Is So Dangerous

ACE inhibitors lower blood pressure by blocking the enzyme that makes angiotensin II. That’s good. But it also reduces aldosterone, a hormone that tells your kidneys to flush out potassium. Spironolactone does the same thing - but even more directly. It blocks aldosterone receptors in the kidneys. So when you take both, your body loses its main tools for getting rid of excess potassium. The result? Potassium builds up. Fast.It’s not just a lab anomaly. In the landmark RALES trial from 1999, patients on spironolactone had potassium levels that stayed higher than those on placebo - and it didn’t fade after a few weeks. It stuck. By month one, the difference was clear. By month six, nearly 1 in 7 patients on the full 25 mg dose of spironolactone had potassium levels above 5.0 mmol/L - the clinical cutoff for hyperkalemia.

And that was in a controlled trial with strict monitoring. In real life? It’s worse. A 2015 study of over 134,000 heart failure patients in Germany found the risk of hyperkalemia was much higher in everyday practice than in clinical trials. Why? Real patients have other problems - kidney disease, diabetes, older age - that trials intentionally exclude.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone who takes this combo will get hyperkalemia. But some people are walking into a minefield without knowing it.- Age over 70: Your kidneys naturally slow down. One study found 10% of elderly patients on ACE inhibitors alone developed severe hyperkalemia (potassium >6.0 mmol/L) within a year. Add spironolactone? The risk doubles.

- Chronic kidney disease: If your eGFR is below 60 mL/min/1.73m², you’re already struggling to clear potassium. This combo can push you over the edge. One study showed these patients had a 3.2-fold higher risk of hyperkalemia than those with normal kidney function.

- Diabetes: High blood sugar damages kidney blood vessels. That makes potassium harder to excrete. Diabetics on this combo are at especially high risk.

- Baseline potassium already above 5.0 mmol/L: If your potassium is already high before you start, adding spironolactone is like pouring gasoline on a fire.

- Severe heart failure (NYHA Class III or IV): These patients often have reduced kidney perfusion. Their bodies are already in survival mode - and potassium control is one of the first things to break down.

One 1996 study of 1,818 outpatients found that 11% developed hyperkalemia on ACE inhibitors alone. Add spironolactone? That number climbs fast - especially if any of the above risk factors are present.

What Happens When Potassium Gets Too High?

High potassium doesn’t always cause symptoms - at first. That’s why it’s so dangerous. You might feel fine. Your heart doesn’t. Potassium controls how your heart muscle cells fire. Too much, and those signals get messy.Early signs? Muscle weakness, fatigue, tingling. But the real danger is cardiac. As potassium climbs above 5.5 mmol/L, your EKG starts to change. Peaked T waves. Then widened QRS complexes. Then - if it keeps rising - ventricular fibrillation or cardiac arrest.

The RALES trial showed something surprising: mortality spiked at potassium levels below 3.5 mmol/L and above 6.0 mmol/L. But here’s the key - even with potassium between 5.0 and 5.5 mmol/L, the mortality benefit of spironolactone still held. That means stopping the drug just because potassium hits 5.1 isn’t always the right move.

How Doctors Are Supposed to Monitor This

Guidelines aren’t vague. They’re specific - and they’re there for a reason.- Before starting: Check serum potassium, creatinine, and eGFR. If potassium is already >5.0 mmol/L or creatinine >1.5 mg/dL, think twice.

- Within 7-14 days: Test again. This is non-negotiable. Many doctors skip this. Don’t.

- After every dose change: Even a small increase in spironolactone from 12.5 mg to 25 mg can trigger a spike.

- Every 4 months: Even if you’re stable, potassium can creep up slowly.

For high-risk patients - anyone over 70, with kidney disease, or diabetes - testing should happen even sooner: within 3-5 days of starting the combo. Some experts recommend weekly checks for the first month.

Also, don’t panic over small creatinine changes. A rise of up to 30% or an eGFR drop of up to 25% is acceptable - as long as potassium stays under control. That’s a key point many clinicians miss.

What to Do If Potassium Rises

Don’t automatically stop the drugs. That’s outdated thinking.- Potassium 5.1-5.5 mmol/L: Don’t panic. Reduce spironolactone to 12.5 mg daily. Keep the ACE inhibitor. Recheck in 5-7 days. Many patients stay on this adjusted dose with no further issues - and still get the survival benefit.

- Potassium 5.6-6.0 mmol/L: Temporarily stop spironolactone. Keep the ACE inhibitor. Recheck potassium in 3 days. If it drops below 5.0, restart at 12.5 mg and monitor closely.

- Potassium >6.0 mmol/L: Stop both drugs immediately. This is an emergency. Go to the ER. You may need calcium gluconate, insulin with glucose, or dialysis.

Some doctors still cut the dose or stop everything at the first sign of high potassium. That’s a mistake. The RALES trial showed the mortality benefit lasted until potassium exceeded 5.5 mmol/L. You’re not just treating a lab value - you’re balancing life-saving therapy against a manageable risk.

What About Diet?

You’ve probably heard: “Eat less potassium.” Bananas, oranges, potatoes, spinach - avoid them.But here’s the truth: dietary potassium restriction has very weak evidence in real-world practice. Studies show it barely moves the needle. A 2,000 mg/day limit sounds strict - but most people don’t even hit that. And if you’re already eating a heart-healthy diet, you’re probably already low in processed foods and high in vegetables - which is good for your heart, even if it’s high in potassium.

Instead of obsessing over diet, focus on what actually works: medication adjustments, monitoring, and avoiding other potassium-raising drugs like NSAIDs, trimethoprim, or potassium supplements.

Newer Options Are Coming

Spironolactone isn’t the only option anymore. Finerenone, a newer mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, was approved in 2021 for diabetic kidney disease. In the FIDELIO-DKD trial, it caused 6.5% fewer cases of hyperkalemia than spironolactone when combined with ACE inhibitors.But here’s the catch: finerenone costs about $450 a month. Spironolactone? Four dollars. For most patients, especially those on Medicare Part D, cost matters. Finerenone is a great tool - but it’s not a replacement for everyone.

Another promising angle: SGLT2 inhibitors (like empagliflozin). The 2022 EMPA-HEART study found adding one of these diabetes drugs to an ACE inhibitor/spironolactone combo reduced hyperkalemia events by 22% over 12 months. It’s not yet standard, but it’s a sign that the future may involve layered protection - not just avoiding the combo.

The Bottom Line

This combination saves lives. But it’s not safe unless it’s managed well. Too many patients are either denied this therapy because of fear - or thrown into it without monitoring.The truth? You don’t have to choose between safety and survival. You can have both - if you’re smart about it. Start low. Monitor often. Adjust, don’t abandon. Know your numbers. If you’re on this combo, ask your doctor: “When was my last potassium test?” If they can’t answer, it’s time to push back.

Heart failure is serious. Hyperkalemia is serious. But neither should stop you from getting the treatment that could give you more years - if you’re watched closely enough.

Written by Guy Boertje

View all posts by: Guy Boertje